Data highlights tamarisk beetle populations within Mojave Trails National Monument

Intern Lauren Casas examines a net with tamarisk beetles in 2022.

By Mary Cook-Rhyne, Education Programs Manager

Introduction

Over four years, interns with our Women In Science Discovering Our Mojave (WISDOM) program returned to five data points within Mojave Trails National Monument to study the presence of the tamarisk beetle (Diorhabda spp.), introduced as a biocontrol against invasive tamarisk trees.

Data collected illustrates that the tamarisk populations have changed dramatically during that time.

Tamarisk trees (Tamarix spp.) are a very hardy invasive species that deplete the natural groundwater reservoirs and outcompete native plants (Eckberg et. al. 2016). The trees were introduced to the US in the mid-1800s. They were originally planted as an erosional control method along the railroad lines in the western US and later as an ornamental tree.

A tamarisk tree at Site 1, Field Day 5, 2023. WISDOM Intern Alyssa Diaz

Tamarisk trees have become well established in Afton Canyon Natural Area in Mojave Trails National Monument along the rail line that runs through the canyon.

Tamarisk diminishes the water supply by establishing deep taproots, leaving less surface water for other species (Southwest Biological Center 2016). Their roots grow into the water table and lose much of that ground water due to their high rate of evapotranspiration. They do not have the natural adaptations that desert plants need to protect themselves from excessive water loss. Additionally, after the leaves fall, they create an overly saline undergrowth which alters the soil, often creating a harsh habitat that is not well suited for native plant species growth.

A close-up of a tamarisk beetle.

Tamarisk beetles were imported by the USDA in 2001 as a biocontrol method to eventually kill trees, within 3-5 years, without the use of herbicides. Tamarisk beetles and tamarisk weevils are known to be established in the canyon and are a management concern for the Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

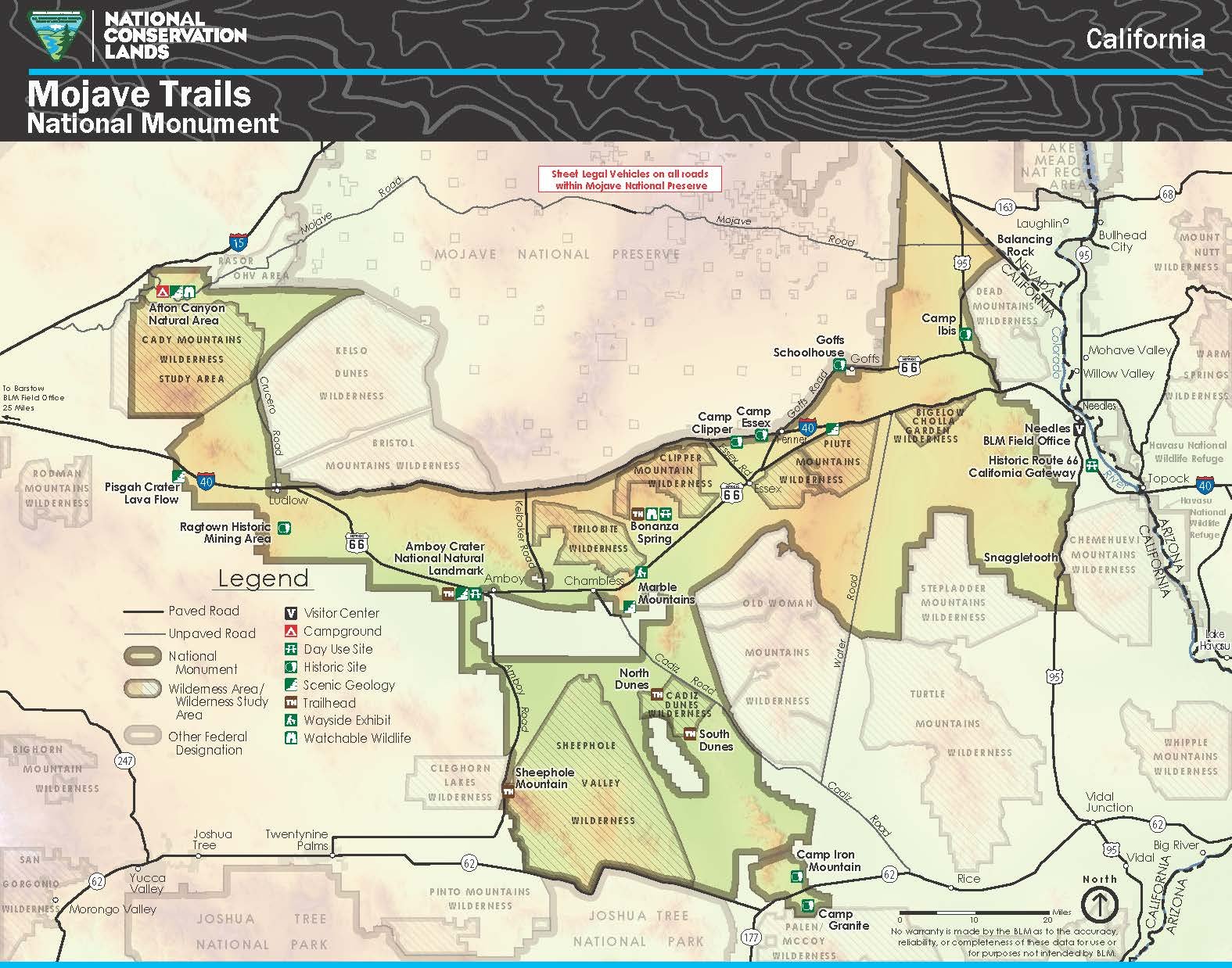

The research area

Mojave Trails National Monument is administered by the BLM and spans 1.6 million acres. It was designated in 2016 by then-President Barack Obama to preserve its natural, cultural, and scenic resource values. Afton Canyon Natural Area contains one of three areas of the Mojave River that flows above ground year-round and is an Area of Critical Environmental Concern (ACEC). The section of the Mojave River in Afton Canyon is considered “eligible” as a Wild and Scenic River under the National Wild and Scenic River Act (BLM 2023). Colloquially known as the “Grand Canyon of the Mojave” due to its rugged terrain and beautiful geologic structures, Afton is a biodiversity hotspot with a multitude of species that live in and visit the area. Additionally, the canyon is culturally significant to many Indigenous tribes within California as a historic trading route and for its natural resources. The canyon has also been used historically as part of the Mojave Road and currently is part of the railroad system.

Interns Kaeliegh Watson and Christiana Saldana collect data in 2022.

Since 2019, 33 Women in Science Discovering Our Mojave (WISDOM) interns have participated in various research projects within Mojave Trails National Monument. The WISDOM internship is run by the Mojave Desert Land Trust and seeks to engage women from underserved communities in studying Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM).

WISDOM research supports BLM in their resource management.

Research goal

BLM has been working to remove tamarisk trees to restore riparian habitat in Afton Canyon (BLM 2023) by using herbicide treatments, prescribed burns, and mechanical removal. In 2016, the tamarisk beetle showed up in Afton Canyon, likely escapees coming from biocontrol efforts further upstream. One method of dealing with tamarisk is through using tamarisk insects as biocontrol. Though the effect of using beetles as a biocontrol method may impact other native species as found by Paxton et. al (2011). Even after being sprayed with pesticides or cut down the trees can still regrow, as in the case of Site 2.

WISDOM interns conducted quantitative biocontrol monitoring surveys of tamarisk beetles (Diorhabda spp.) and tamarisk weevils (Coniatus splendidulus) at five points within Afton Canyon during the summer months in 2020, 2022, and 2023. This study also determined where new populations existed, and where beetles had yet to colonize. The BLM is using these data to evaluate how this biocontrol is interacting with their other tamarisk management efforts.

Figure 2. Tamarisk study locations throughout Afton Canyon.

Interns had to conduct sweeping sets of tamarisk trees to count insects. Sweep-netting protocol was developed by Rivers Edge West, providing accurate population estimates and has higher probabilities to positively sample very low populations. The information gathered was also shared with Rivers Edge West whose mission is to restore riverside (riparian) ecosystems through education, collaboration, and technical assistance.

Results

Conclusions

Site 2, Field Day 1, 2023. WISDOM Intern Anabelle Merrell next to tamarisk tree regrowth after the 2022 field season tree removal by the BLM.

Between 2020 and 2023, the tamarisk populations have changed dramatically, most likely due to a multitude of factors that are yet to be well understood.

Site 1, the furthest site west, has seen a steady beetle population size, though somewhat reduced in 2023. Site 2 had a large beetle population size before BLM tamarisk tree removal activities in 2022, with tamarisk beetles returning to regrowth areas this year. The sites further east in the canyon (Site 4 & 5) had the largest beetle activity in 2022; the beetle population has dramatically decreased during the 2023 survey season. Site 5, overall, had the largest beetle population over the study. Defoliation of tamarisk also does not appear to affect the beetle populations. Overall, it appears that the 2022 study season saw the largest numbers of insects found across all 5 sites.

No data was collected in 2021 to focus on other projects within Afton Canyon Natural Area.

Data does not show there to be any correlation between temperature and the population size of the beetle. The average daily temperature in 2020 was 102.4 degrees. The average daily temperature in 2022 was 95.6 degrees. In 2023, the average daily temperature was 97.5 degrees.

Further study of Diorhabda populations is needed to provide a better understanding of beetle movement and their effectiveness in impacting tamarisk trees in Afton Canyon. By continuing the study, longitudinal data will help us understand the influence that defoliation and dieback of tamarisk has on the surrounding plant communities. This will allow the BLM to have a better understanding of riparian habitat restoration and improving integrity of native plant communities throughout Afton Canyon.

WISDOM is supported by the Conservation Lands Foundation and is a collaboration with the Bureau of Land Management.

Explore an interactive storymap about the tamarisk surveys.

Read more about the WISDOM program here. Interested in becoming involved? Write to Mary@mdlt.org

Sources and further reading:

Bureau of Land Management. 2023. Field Office, Fire and Fuels Reports, Desert Advisory Council. www.blm.gov/sites/default/files/docs/2023-08/August_2023_DAC_Report_508.pdf. August 2023.

Di Tomaso, Joseph M. “Impact, Biology, and Ecology of Saltcedar (Tamarix Spp.) in the Southwestern United States.” Weed Technology, vol. 12, no. 2, 1998, pp. 326–36. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3988397.

Eckberg, Jason R., and Nicholas A. Rice. “NORTHERN TAMARISK BEETLE (DIORHABDA CARINULATA) EFFECTS ON ESTABLISHED TAMARISK-FEEDING INVERTEBRATE POPULATIONS ALONG THE LAS VEGAS WASH, CLARK COUNTY, NEVADA.” The Southwestern Naturalist, vol. 61, no. 2, 2016, pp. 101–07. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26748494. Accessed 6 Oct. 2023.

Paxton, Eben H., et al. “Tamarisk Biocontrol Using Tamarisk Beetles: Potential Consequences For Riparian Birds in the Southwestern United States - Control Biológico Del Tamarisco Por El Escarabajo Del Tamarisco: Consecuencias Potenciales Para Las Aves Ribereñas En El Sudoeste de Los Estados Unidos.” The Condor, vol. 113, no. 2, 2011, pp. 255–65. JSTOR.

RiversEdge West, Colorado Department of Agriculture, Northern Arizona University, and University of California-Santa Barbara. 2020. Tamarisk Beetle and Tamarisk Phenology Monitoring Protocol.

Southwest Biological Science Center. 2016. Southwest Riparian Zones, Tamarisk Plants, and the Tamarisk Beetle. United States Geological Survey. https://www.usgs.gov/centers/southwest-biological-science-center/science/southwestern-riparian-zones-tamarisk-plants-and

United States Department of Agriculture. 2023. Saltcedar. https://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/terrestrial/plants/saltcedar

United States Forest Service. 2023. Fire Effects Information System (FEIS). https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/tree/tamspp/all.html